The network of communication that connected the Indian reservations of the west facilitated the dissemination of the 1890 ghost dance, a religious movement that spread as fast as any in American history. The ideas of the movement originated in the Great Basin from a man named Wovoka (or Jack Wilson) on a reservation in Nevada and were carried across the Rockies onto dozens of reserves on the Great Plains and into the minds of thousands of people. Wovoka, who was thought by many to be a new messiah, prophesized the coming of a regenerated earth, apart from whites, if the Indians danced according to his instructions. Information about the movement spread among reservations. Skeptical tribal leaders sent out investigators to travel hundreds of miles to meet Wovoka to determine the truth. Those living east of the Rockies relied on the relationships they had built with the western tribes to find him. The expanding railway system made these journeys much easier. Correspondents, who for years had used letters to share news with friends and family on other reserves, exchanged ideas about the new messiah. So many letters regarding the ghost dance reached reservations that some Indian Affairs agents censored the mail in an effort to limit the movement’s progress. This shared purpose, to communicate what the ghost dance was to others within their developing intertribal community, brought Natives throughout the American West closer together.

“We have always had different roads. The Great Spirit when he created us gave us forms of worship; the whites one, the reds another. We worship in the form of dancing; you worship in the form of prayer. We are not responsible for our different ways. As the reds have their way to worship a god, so have the whites theirs. They do not like ours and instead of scolding us when they are angry, as they think they do, they scold the Great Spirit. Last summer we thought it our duty to have one of these dances…the privilege was denied and we accepted the denial. We want to worship this summer. There is nothing bad in it.” – Big Tree, Kiowa Chief, addressing Indian Affairs Inspector William Junkin at a council, June 24, 1890.

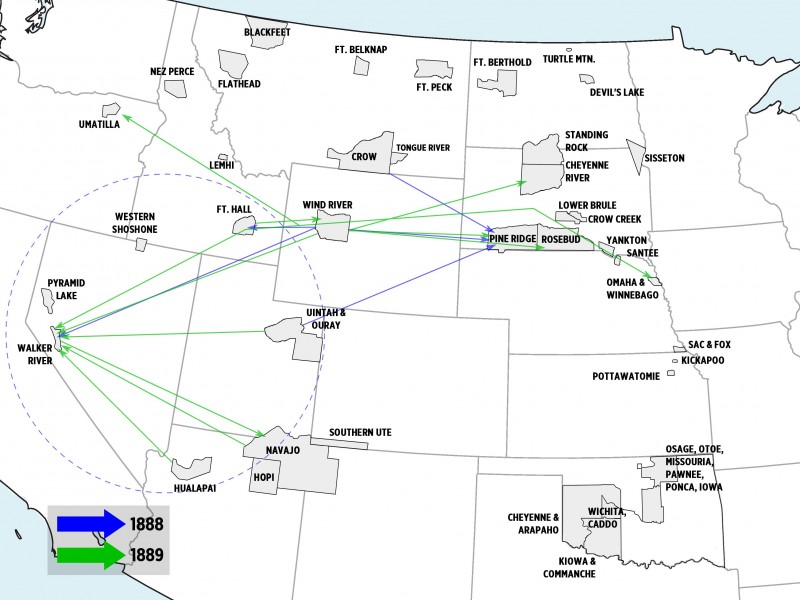

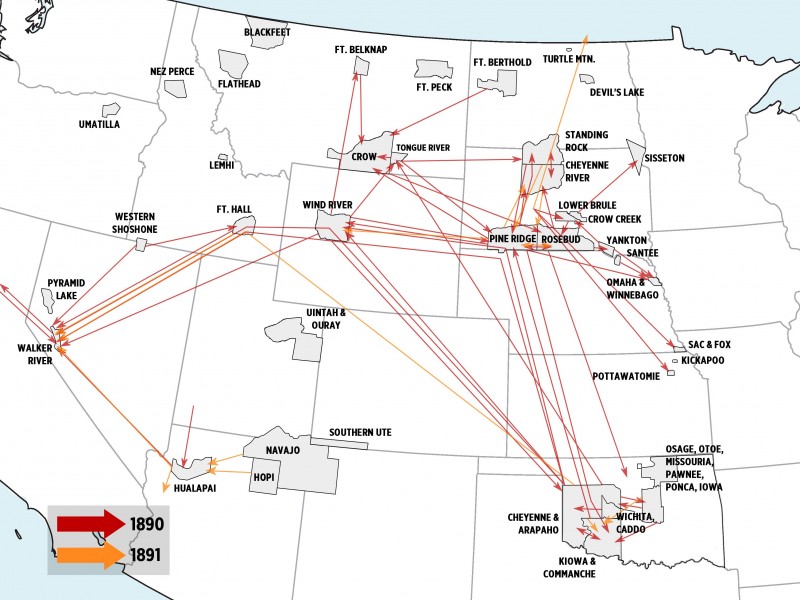

These maps visualize the documented visits between reservations that were made because of the ghost dance. Each arrow represents one or more than one visit made. By late 1888, Wovoka’s message had left the Walker River Agency in Nevada and reached nearby reservations. Information also traveled across the Rockies and into the Plains before 1889. By the end of 1889, delegates of Lakotas, Northern Cheyennes, Northern Arapahos, and dozen of other groups visited Wovoka in person in Nevada. Many arrived with the help of the railroads.

Some trips were made by Natives in order to investigate the new religious movement and discover the truth about Wovoka. Many traveled to deliberately spread news about the ghost dance to other Native groups. A few traveled to convince others not to dance.

News of the dance filled reservations in 1890. Intertribal ghost dancing became popular on many reservations. The “Messiah Craze,” as the press called the movement, drew the attention of whites and government authorities. Despite Indian Affairs’ efforts to curb the spread of the movement, the ghost dance remained a topic of discussion on reservations throughout the 1890s.

“My Sister we have always lived in tribulation, still you remembered me even though I have left you. It gives me great pleasure to receive a letter from you as it is just as if I had seen you. In addition to answering your letter I would like to inform you of something. It is in regard to the dance which created a commotion up there. It is the truth and will surely come to pass…Now you must use every effort to come in possession of some Eagle’s-down, and have them in readiness. From the time the grass starts you must be on the lookout and when a thunder storm comes you must attach them to your hair. Take care that you heed what I say.” – Many Eagles (or Plenty Eagles), an Oglala Lakota living at Pine Ridge, to his sister, March 5, 1891.

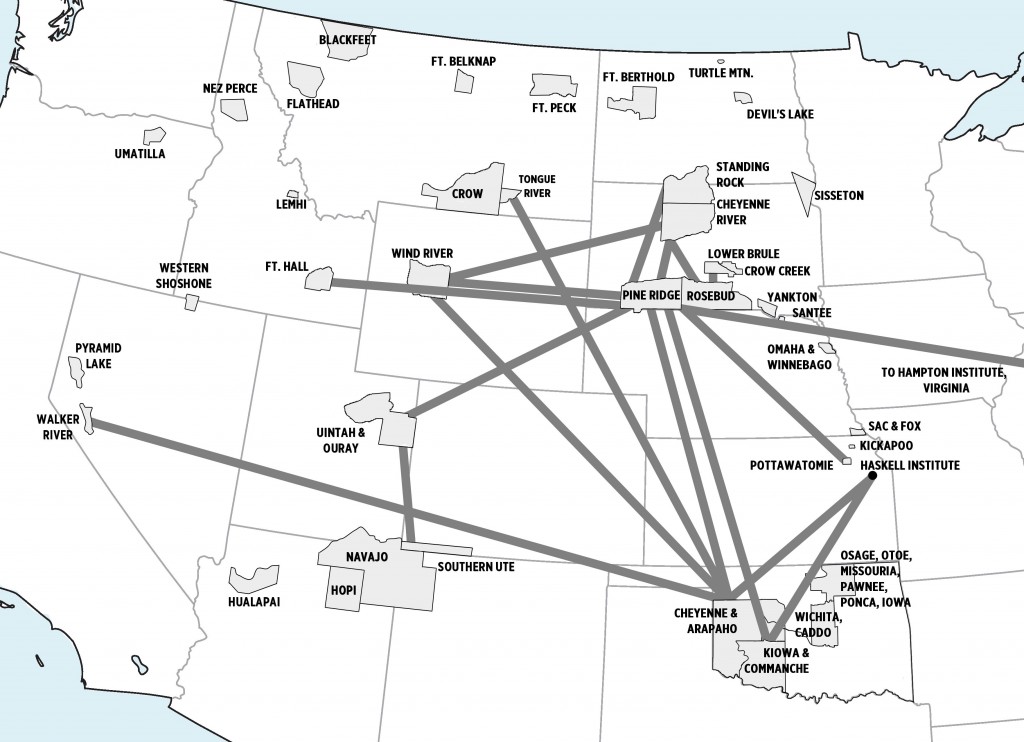

Letter writing, which had become a common part of life for many Natives by the end of the 1880s, was the primary mover of ghost dance information. Letters connected reservations, allowing groups to communicate the meaning of the dance quickly. The map below visualizes the network of ghost dance correspondence. Each connection represents one or more than one letters sent between Indian reservations that spoke of the new religious movement.

By the end of 1890, most Plains Indians had heard about the ghost dance and thousands believed in its promises. No other religious movement reached so many Natives in such a short amount of time. The dance not only affected the southern and northern divisions of the Cheyennes and Arapahos or the Paiutes who inaugurated the first dances, but also over thirty other tribes including the Shoshones, Bannocks, Utes, Mohaves, Hualapais, most bands of the Lakotas, Assiniboines, Gros Ventres, Arikaras, Mandans, Kiowas, Caddos, Wichitas, Comanches, Apaches, Poncas, Pawnees, Otoes, Osages, Kickapoos, and others.

LINKS OF CORRESPONDENCE CONCERNING THE GHOST DANCE, 1889-1894

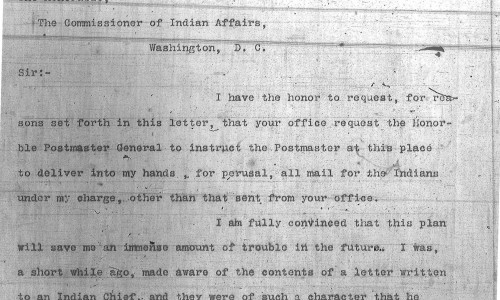

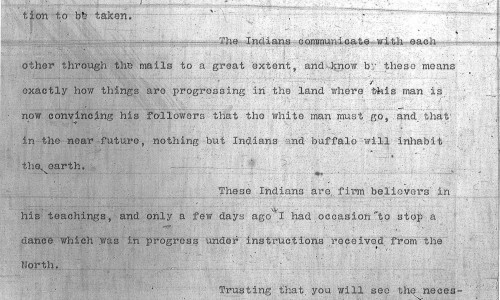

Indian Affairs agents were determined to stop this flow of information between reservations. They realized that letter writing needed to be controlled to halt the progress of the ghost dance. So many letters reached the Kiowa, Comanche, and Wichita Agency that the agent there, Charles Adams, requested the power to censor the Indians’ mail. He wanted the Postmaster General to instruct the postmaster at Anadarko, Oklahoma to deliver all the mail sent to the Indians into his hands for his “perusal.” He thought the Indians were “in an unsettled frame of mind” and “steps should be taken to avoid future trouble.” For Adams, the solution was to prevent his population from communicating with the outside world, “I consider this the principal precaution to be taken,” he wrote.

By 1890, thousands of Natives had attended school and learned how to read and write. Hundreds had left their reservations to attended boarding schools. Whites hoped that education would remove Indian culture from their students’ minds and they saw the ghost dance as the antithesis of education – it flourished “only in the soil of superstition.” The educated, most whites assumed, could not believe in such things.

But many educated Natives believed in the ghost dance movement and they used their education to propagate it. Even some former students of the Carlisle Indian School, like the Lakota Raymond Stewart and the Southern Arapaho Smith Curley, became letter writers for ghost dance leaders. Whites were surprised to discover that Indian groups were using the government’s “civilizing” education to their own advantage by spreading the ghost dance’s message through letters. Literacy was used by Native Americans to foster their culture. They did not allow white education to destroy their way of life.